The Brutal Truth About Why Your Efforts Go Unnoticed

Hard work alone won't save you. The employee who silently handles everything often becomes invisible—until they're gone.

I've watched people get fired who were carrying entire departments on their backs. Not for mistakes, not for slacking — just because at some point they became inconvenient. Too independent, too visible, too expensive. Or the opposite — so invisible that people only remembered them when something broke.

This piece is for people I know personally, and for those I don't know but will recognize from this description. For people who do good work, sometimes the work of two or three, and still feel undervalued. I want to share what I've seen — from both sides of the table. Not to lecture, but to warn.

The quiet heroes and their biggest trap

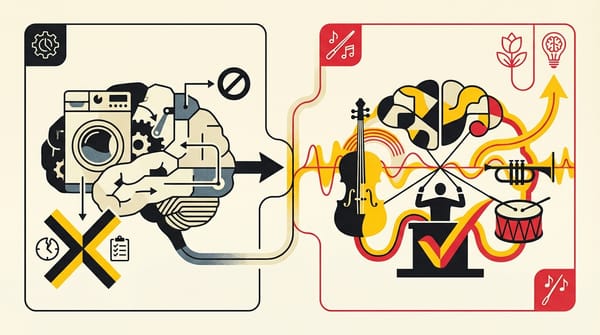

There's a type — the person who quietly handles nine out of ten tasks. No one notices because everything just works. Then a problem comes up, and they go to their manager — because they need help or a decision that's above their pay grade.

Here's what happens: the manager only sees this person when there's a problem. Again and again. Not because there are many problems, but because those other nine tasks went by without applause. A picture forms in the manager's head: this employee is about problems. Not solutions, not results. Problems.

It's unfair. But it's reality.

I'm not saying you should brag about every closed ticket. But if you work in silence for months and only show up with bad news — the person on the other side develops a warped perception. And they're not even to blame, it's just how brains work: we remember what triggers emotions, and quiet good work doesn't trigger anything.

"I can handle it" — three words that dilute you

Good specialists often take on more than they should. Not because they enjoy it, but because they see a problem and can't walk past it. The finance person starts managing processes, the developer becomes a project manager, the designer handles client communication.

From the outside, it looks like initiative. From the inside — like dilution. You're spending energy on things where you're not the best, instead of deepening what makes you irreplaceable. And six months later, you're in a situation where people value you for a little of everything and nothing specific. That's the most vulnerable position when cuts come.

Define your territory and go so deep that your absence would hurt.

A marathon with no finish line

I've seen people close tasks like a conveyor belt — one after another, no breaks, no weekends, no asking "what's the point?" They genuinely believed that quantity was proof of value.

But work isn't an endurance race. Someone who focuses on three things and does them well is more visible than someone who spreads themselves across twenty tasks. Paradox: the one who does less but with precision — grows faster. And the one who does more than anyone — burns out first, and their departure often surprises no one, because they stopped being visible long ago behind their endless busyness.

What usually goes unsaid

Now — a layer deeper, the stuff people usually don't talk about.

In 2025, Meta fired 3,600 people under the banner of "raising performance standards." Among them were people with excellent reviews, bonuses, years of flawless work. Microsoft, Amazon, Goldman Sachs — same story. They call it "performance-based," but really they're replacing expensive with cheap.

You can do everything right and still end up on the chopping block. Not because you're bad, but because you cost too much. Or because someone above you feels threatened — you're too competent, too independent, you see too much of the big picture. For a good manager, that's a gift. For a weak one — a reason to get rid of you.

And there's another trap, the most painful one: burnout from trust. They trust you — so they give you more. You handle it — so they add more. And more. At some point, the trust that should have been recognition becomes just overload. You burn out not from being treated badly, but from being treated well. Because no one considered that trust has limits too.

From the other side of the table

I've sat in that chair myself — been a manager, hired, fired, built teams. And here's what I understood long ago and still believe is the only right approach: if a specialist delivers results, my job is to adapt to them, not break them to fit me.

I've had people who grumbled, snapped back, glared through meetings. And still delivered work I could be proud of. Did I care? Sure — it's nicer to work with someone who's both skilled and pleasant. But in practice, those grumblers were often the most reliable. They didn't smile for the sake of it, but they did their job so well I could sleep at night.

The problem is that few people take management seriously as a profession. Leading people is a skill you need to learn, but most managers ended up in that chair by accident: they were good at their job, got promoted, and then — figure it out yourself. So someone who was writing code or crunching budgets yesterday is supposed to understand motivation today, read the team's mood, adapt their approach to each person. No training, no mentor, often no desire.

People are people. Not all managers are evil or stupid. Many just don't know how. And the ones who suffer most are those who work the hardest.

Why I'm writing this

Not to teach. Not to give you a five-point list and say "follow this and you'll be fine." It would be a lie to promise that doing everything right means you'll definitely be valued.

I'm writing this because I know people who work with integrity — quietly, honestly, sometimes to exhaustion — and feel like it's not enough. I want them to know: I've seen it. From both sides.

And the only thing I can say for certain: pay attention to how you're perceived. Not because you need to play politics, but because good work that no one knows about is a tree falling in a forest where no one's around.

The sound was there. But no one heard it.